Above, at the wedding of her granddaughter Kate Patrick Meyers in 2017, Mary “Ma” Patrick danced all night at the age of 86.

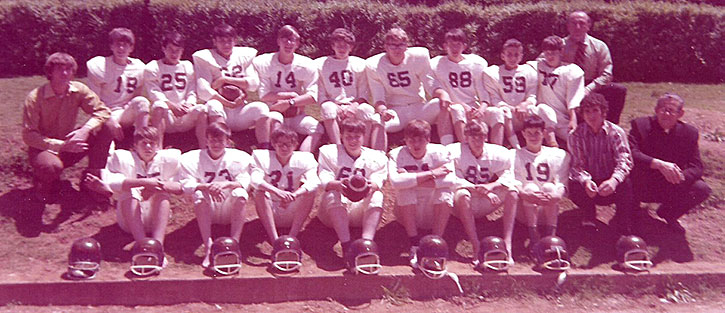

We were a ragtag bunch.

Our uniforms were at least 10 years old. Penn State-plain. White, with blue numerals that were too small, that looked like they were hand cut from a stencil. Stitched up where tears had occurred over the years.

And blue helmets with no decals, scuffed from years of use, mostly with minimal actual padding, just leather straps inside to keep your skull from rubbing the plastic.

The facemasks looked like they were afterthoughts because they were. Added on when they became required. Look up early Gale Sayers highlights and you’ll get the idea. (You’ll also get to see a truly amazing running back.) Two simple plastic bars connected by a couple of plastic tines.

For years, St. Joseph’s school had thrived, highly regarded for its discipline and high standards for education and character. Almost all of the Catholic parents in Fayetteville — and some from the smaller towns out in the country — sent their kids to St. Joe, from Kindergarten to ninth grade. They wanted what St. Joe’s offered and, on top of that, to have their kids learn their faith. We were instructed by a convent of seriously dedicated nuns.

The sports teams were pretty strong. The football team even won a conference championship in the mid-60’s, playing against public school teams like Farmington, West Fork, Prairie Grove, Lincoln, Gravette, Gentry, even Mountainburg.

But, my ninth-grade year, we were not that.

By 1970, things were different. For many reasons — the nuns had left after having a run in with our pastor for one thing — enrollment had dropped drastically, and the school was having financial difficulties.

It survives today, however, after contracting to a K-6 school. In fact, the enrollment has surged in recent years, which I’m glad to see.

Somewhere in a hall in the deep recesses of the school, our ninth-grade pictures are still hanging. There were about a dozen of us that had been there for a long time. There were also a few added in that had been enrolled after being expelled from other schools. The old reputation for discipline was still there but really had gone away with the nuns.

I’m not sure when I started playfully calling my folks Ma and Pa. No doubt I blurted it out one day out of silliness, when we were all carrying on around the house talking like the Beverly Hillbillies or something.

Before long, everybody at school was calling them Ma and Pa. You see, our house was where the guys almost always got together. I lived a couple of blocks away from school.

In the fall of ‘70, our little gang formed the nucleus of the last St. Joseph’s Junior High Blue Panthers football team. We had no idea that was the case at the time, but it turned out that way.

There were 16 of us at the beginning of the season. Seven in ninth grade, three in eighth grade, four in seventh and two in sixth. The two sixth graders were ineligible for conference games, so they only played in a pinch. They helped us practice.

One of the eighth graders broke his arm in the second game, so for most of the season there were just 13 of us available for action.

Our practices were held in the fenceless outfield of an old softball diamond behind the Veteran’s Hospital, a good three miles from school.

We had no home field. We played all of our games in visitor’s white.

Normally, Fayetteville High School let the Panthers play one game on their field, for Homecoming. But that year, it rained for several days prior to our scheduled date and the FHS officials decided they didn’t want us chewing up their sod on Tuesday night when they had a junior high game set for Thursday and a high school game at home on Friday.

So, our Homecoming in 1970 was held on the road, at Prairie Grove. It was somehow fitting.

Now, the school had no buses or vans to tote the team around in. That was up to the parents. It usually took two or three station wagons and a van to get everybody to the ballgames. One of those station wagons, of course, was Ma and Pa Patrick’s.

Ma was an enthusiastic supporter, as loud and boisterous as any. Pa was a little less vocal, but just as enthusiastic. They both got into it. But then, they had a lot invested in the program. I was the nominal quarterback and my little brother Mike, a seventh grader, was a tackle of sorts.

We all had nicknames. I was Morton, named after Dallas Cowboys quarterback Craig Morton, who had the unenviable task of following Hall of Famer Roger Staubach. Morton had a tendency to get the nose of the football down and his passes would wind up at the feet of his intended receiver. I made more than a few throws like that in practice one day and suddenly had a new nickname. They even insisted that I wear his number, 14.

The guys knew it would irk me too because I was not a Cowboys fan. In fact, when I was asked which was my favorite team, I would inform them it was whoever was playing against the Cowboys that week.

We had Ole Weird Harold at fullback, Stub at tight end, Tom M or Mom, at tailback. Eli and his little brother Scotty were the wide receivers. Gabe, all 6’2, 225-pounds of him, was pretty much our line himself, holding forth with a rag-tag bunch that ranged from the downright scrawny (Peter Pod) to the downright malicious (Beater) and the rotund (Big Jon) along with Mike, whom I called Mikey D, taking advantage of his middle name, Donathan of all things.

We won nary a game in 10 tries. We failed to score on several occasions and never scored more than once in a game. We did hold a lead one time.

Now, I’m not sure when Ma Patrick first unleashed her cry of pride for her sons. Heck, it may have been when we staggered onto the field for our first game at Mountainburg. Shoot, it’s just as likely she cut loose with it after Mountainburg ripped us 30-0, breaking a 15-year drought against teams from St. Joe.

We didn’t have to win for Ma to be proud.

I didn’t actually hear it. But, later, I found out that sometime that opening night — probably repeatedly — Ma bellowed:

“Mother’s proooooouuuuuuud!”

Mike and I had heard it before. She blurted it out at home, usually in the over-blown excitement over some little something we had done well.

She never just said it, either. She hollered:

“Mother’s proooooouuuuuuud!”

Often, it was something my little sister Jodi, a toddler about that time, had done.

When we were young, it was wonderful to hear. It made us laugh. It made us warm inside. She was shouting to the rooftops how proud she was of us.

But we were in junior high. We were too old for it now. And in public? At a football game? With all our friends around?

Mike and I were mortified. At least on the surface, we were. Deep down, it still had its effect on us. We loved it.

And the rest of the team, the other parents and the cheerleaders loved it too. It became all the rage. Before long, all the other mothers with half a larynx were hollering, “Mother’s proooooouuuuuuud,” when moved to do so by something — good or not so good — on the field.

By midseason, all five or six of the cheerleaders were joining in.

At our muddy Homecoming on the road, there was a chorus of “Mother’s proooooouuuuuuud” pronouncements directed at me during the halftime ceremonies. As the team captain, I was chosen to crown the Homecoming queen, Debbie, whom Gabe called Shrimp because of her diminutive stature. The crowning elicited the call from the whole team. They got a kick out of it. The Prairie Grove folks were probably amused.

I wasn’t particularly.

Our last game of the season was against the mighty Farmington Cardinals, who came into the finale undefeated. They hadn’t even been scored on, in fact, over the previous five games. We didn’t hold out much hope.

We got the ball first, around our own 20. Now, we were a passing team. In a game featuring eight-minute quarters, on a team that was lucky to score at all — let alone win — I probably threw over 20 passes a game. Of course, for some inexplicable reason, the coaches — our assistant pastor Father Cooper and a couple of volunteering alums — also let me call my own plays.

The only way we ran as many plays on offense as we did was because the other teams would score so quickly.

I usually wound up running for my life, getting smeared or flinging the ball where a receiver was supposed to be. Generally, Eli was the best at being where I expected him to be and somehow coming up with the ball. He was the shortest guy on the team, but he had the biggest hands. He made some spectacular catches, I’m told. I didn’t see a one.

He told me years later, he would look back for the ball and all he would see was a hoard of opposing players and, out of the pile like someone spitting a watermelon seed, here came the ball.

I played every down of the season, as most of the guys did. I came out for one play. I think it was at Lincoln. Another muddy night on a field that was adjacent to a cow pasture. There was a smell.

The water pooled at the sidelines at the 50-yard line. On a keeper, I was knocked down right into that mess on the Lincoln sideline. I came up covered in mud. And I couldn’t see through my safety glasses. I had to come out just to get cleaned up.

I told Tom M I had to come out and the coaches moved him to quarterback. He begged me to stay in the game, but I couldn’t. The guys told me later, he could barely talk in the huddle. He wound up running the same play to the other side.

We traded places.

Anyway, at Farmington, the last game of the season, our first play was a slant over the middle to Tom. The play worked maybe once every eight times we tried it. Generally, I misled the receiver, the receiver stopped, or a linebacker got in the way.

But this time, everything fell into place. Tom was at full speed, I somehow got him the ball, Gabe cut down the linebacker and I even got to see Tom catch it. I also got to see him hit the seam and sprint over 70 yards to the Farmington 1-yard line.

Talk about mothers being proud.

I wasn’t sure whether someone caught Tom, or he just collapsed. He may have hyperventilated. I tried to get him to take it the rest of the way on the next play, but he could hardly speak. “No,” he gasped. “You.”

So, I called for a naked bootleg — actually, all of our bootlegs were naked. The blocking was almost non-existent. Stub told me once that his favorite block was the lookout block. He would miss the defender then turn around and yell, “Look out, Morton.”

I took the snap and, instead of rolling out to the strong side, I just sprinted to the opposite corner. I got wiped out at the pylon, but somehow got into the end zone.

We actually had a lead! And we’d scored against Farmington.

Problem was, it only made them mad. By the start of the fourth quarter, it was 56-6.

The one time, however, that I remember Ma’s “Mother’s proooooouuuuuuud!” the most was when she didn’t shout it.

It was at West Fork. Before the game, one of our coaches pulled me aside with the receivers and told me that I should start lobbing my passes down the field to allow our receivers to run under them, fade routes. He figured it would take advantage of our guys’ speed and quickness. And I could get rid of the ball quickly.

Problem was, there was no accounting for the fact that our receivers were small and would lose any jump ball for possession.

I wound up throwing eight interceptions. One actually bounced off the top of Eli’s head 20 yards downfield.

Once again, we lost badly. At the end of the game, we slinked off the field, heads down, shoulders drooping.

The parents and cheerleaders gathered around us. Ma sought me out, put an arm around me and told me, with heartbreaking sincerity, “Mother’s proud, son. You tried hard. You did your best. You did good.”

In the years to follow, Ma engaged in a heavyweight fight, psychologically and physically, with cancer. Over time, she lost most of her colon, had cells removed from each breast, developed lymphoma then pancreatic cancer.

She battled it into her 80’s, through Pa’s death, due in large part to prostate cancer, in 2014. Through weddings and births, joys and heartache.

She instilled a strong faith in all four of her children, who each fell away for a while, but all came back around more faithful than before.

Around New Year’s, she suffered a light stroke, which didn’t debilitate her right away. We brought her to Little Rock from Fayetteville for rehab, amid her protests. She had lived in her house near the school for over 50 years. In fact, the school and church were moved but we didn’t.

Mike, Jodi and my youngest brother Jon did most or all of their growing up in that house. And Ma didn’t want to leave it.

We figured — and told her — after she rehabbed and regained the strength in her right arm and leg, she’d be back home, maybe in a month or six weeks.

She never did go back.

The effects of the stroke, perhaps in conjunction with the lymphoma and the pancreatic cancer, eventually got her.

It was hard at the end. She would wail in pain and frustration.

She lingered for five days in hospice, surrounded by her kids and her grandkids. As was the case when Pa died, God blessed us, their children, to be at her bedside when he took her home on March 3 at 3 o’clock in the afternoon.

She was an amazing woman and there’s so much more I could write about her.

For now, I am so “proooooouuuuuuud!” to be her son.

Happy Mother’s Day in heaven where all is bliss. I love you.

Editor’s note: This is a revised version of a column published in the Benton Courier in 1990.